The Orange Ouevre of Alice Coltrane

Dissecting the symbolism behind the spiritual jazz musician's imagery

The Art of Cover Art is and will continue to be a free resource for all readers. If you have the means this month, consider upgrading to a paid subscription to support my work. A small donation to my ongoing coffee fund is also always appreciated. Happy reading!

Spiritual jazz was born during the Civil Rights Movement in 1960s America. Amidst the thick of racial injustice while personally fighting a drug addiction, tenor saxophonist John Coltrane sought connection with a higher power. Blending African and Asian musical influences, a movement followed, featuring the likes of Sun Ra, Don Cherry, Sonny Sharrock, and, most importantly, Alice Coltrane. Dismissed by the mainstream jazz community due to misogyny and the shadow of her late husband, Alice pushed the boundaries of what the genre could become, sonically and visually.

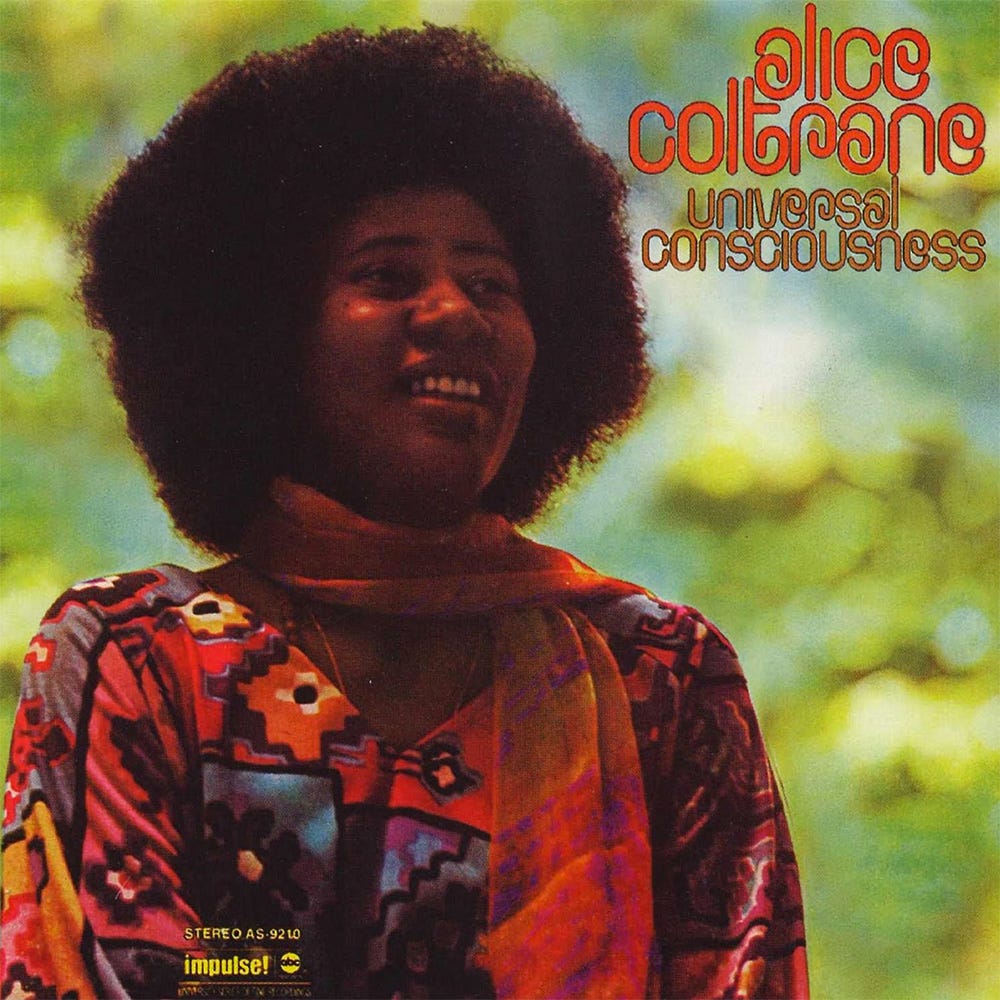

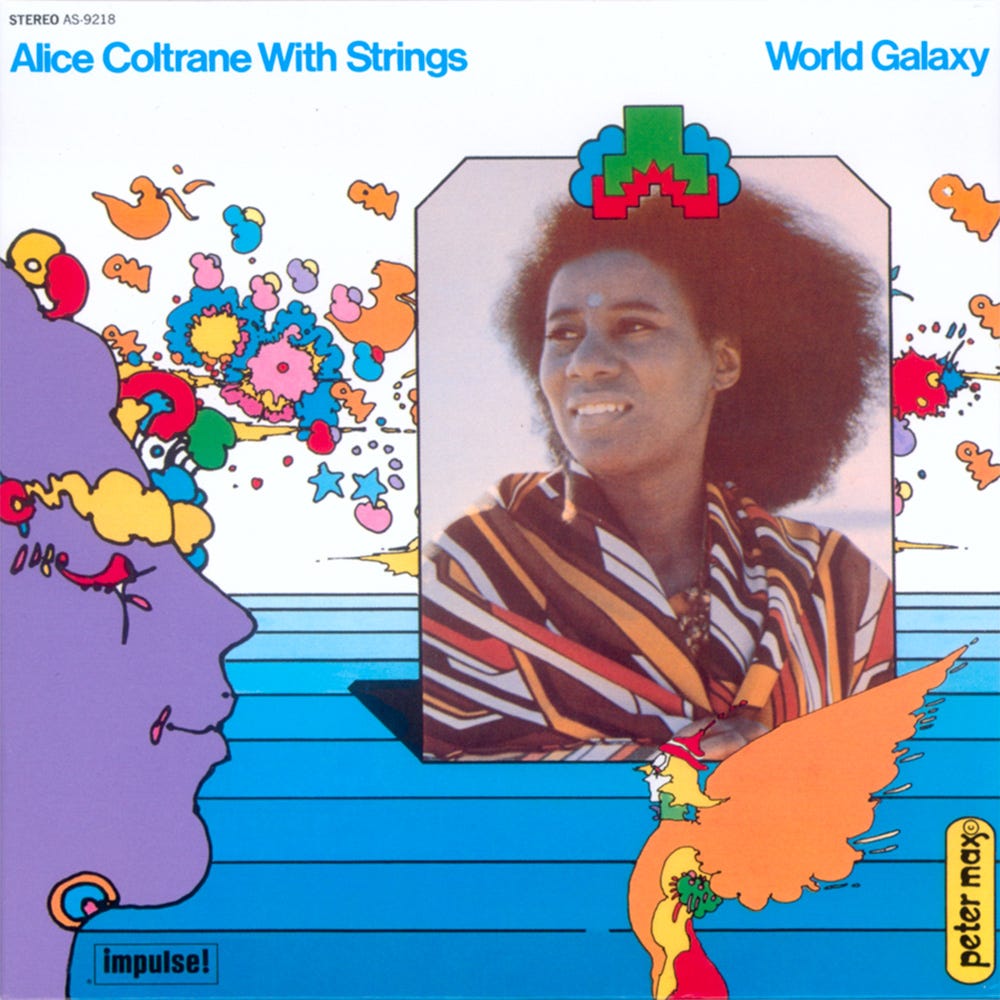

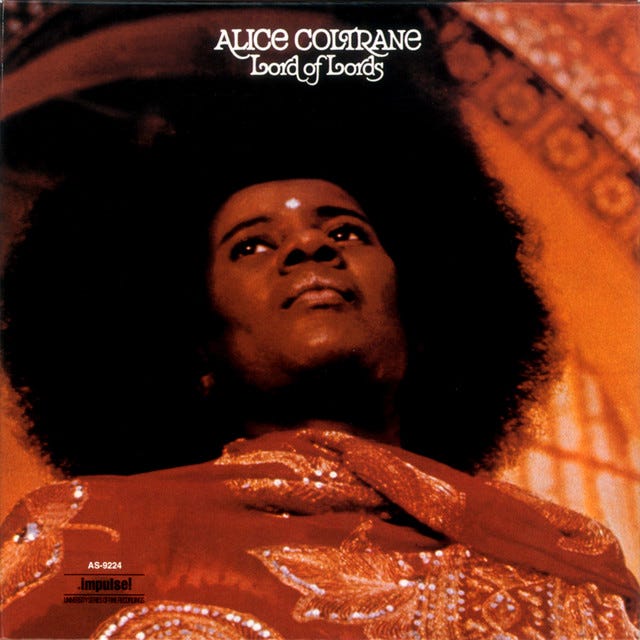

Looking at Alice Coltrane’s discography as a whole, we see a grand sense of symbolism alongside a warm, welcoming orange color palette. Yet, each album was visually crafted by a different set of designers and photographers each time. Rare for such a cohesive body of work. One artist, Phillip Melnick, appears twice, on Universal Consciousness and Lord of Lords. Coltrane’s first creative direction credit doesn’t appear until 1976 on Eternity.

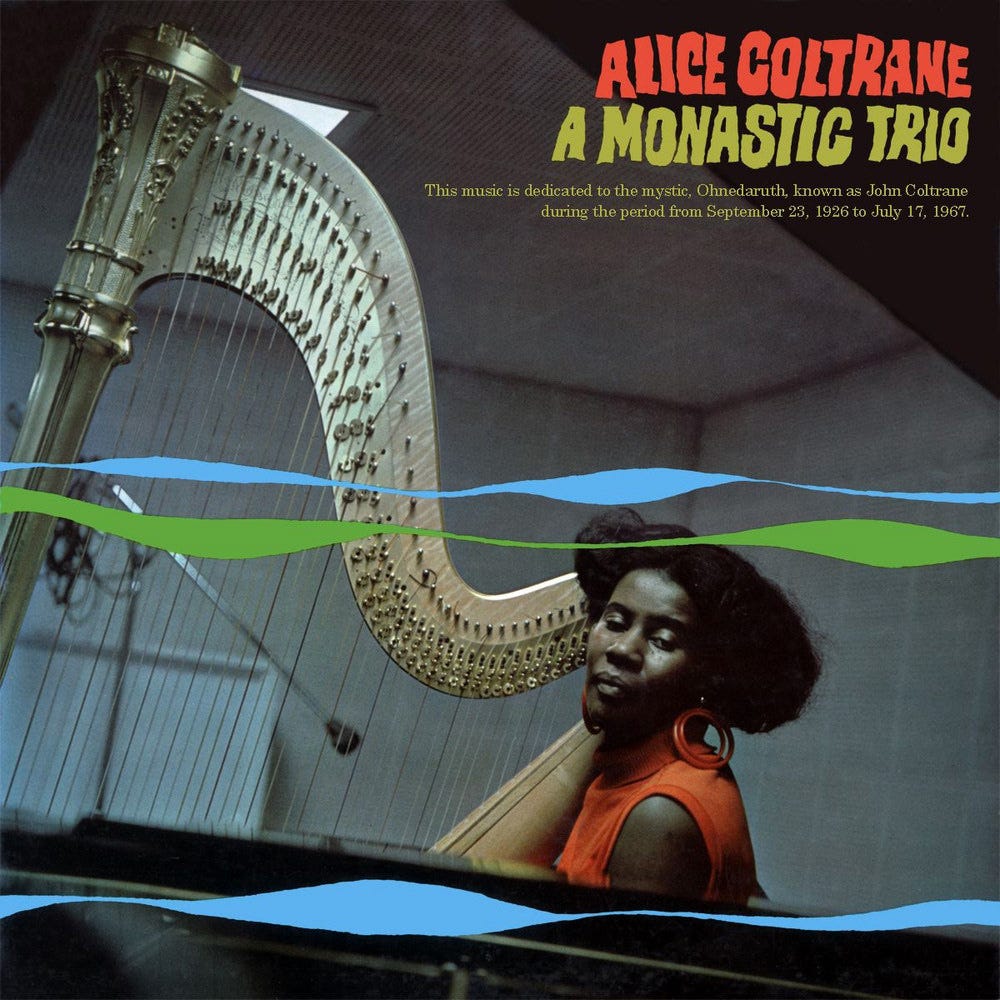

Compared to contemporaries like Pharoah Sanders and Don Cherry, Coltrane’s spiritual vision stands apart. The cover of her debut album, A Monastic Trio, blends in with the jazz styles of the era. Look at any Impulse or Blue Note record cover from the late ‘60s, and you’re bound to see a photo of the musician playing their signature instrument. Here, we see Coltrane playing the harp, yet a set of thin green and blue ribbons dance across the cover, signaling something otherworldly.

After John’s sudden death, Alice found spiritual guidance amid intense grief under the guru Swami Satchidananda. This cosmic journey led her to India, where she discovered a higher religious calling. She adopted the name Turiyasangitananda and, in 1975, opened The Vedantic Center in California. This transcendent new chapter in Coltrane’s life is unmistakably reflected throughout her career’s cover art.

Alice and John were close friends with Indian musician Ravi Shankar (they would go on to name their second son after him). His classical meditative influence is no doubt reflected in the Coltrane ouevre. The cover for Shankar’s second album, The Sounds of India (1958), is such a vibrant atmospheric image, shot in a studio to imitate a warm pink Indian sunset with deep shadows. Alice’s seminal 1971 album, Journey In Satchidananda, is visualized along the same lines. A soft red background encompasses Coltrane as she stoically looks off-frame.

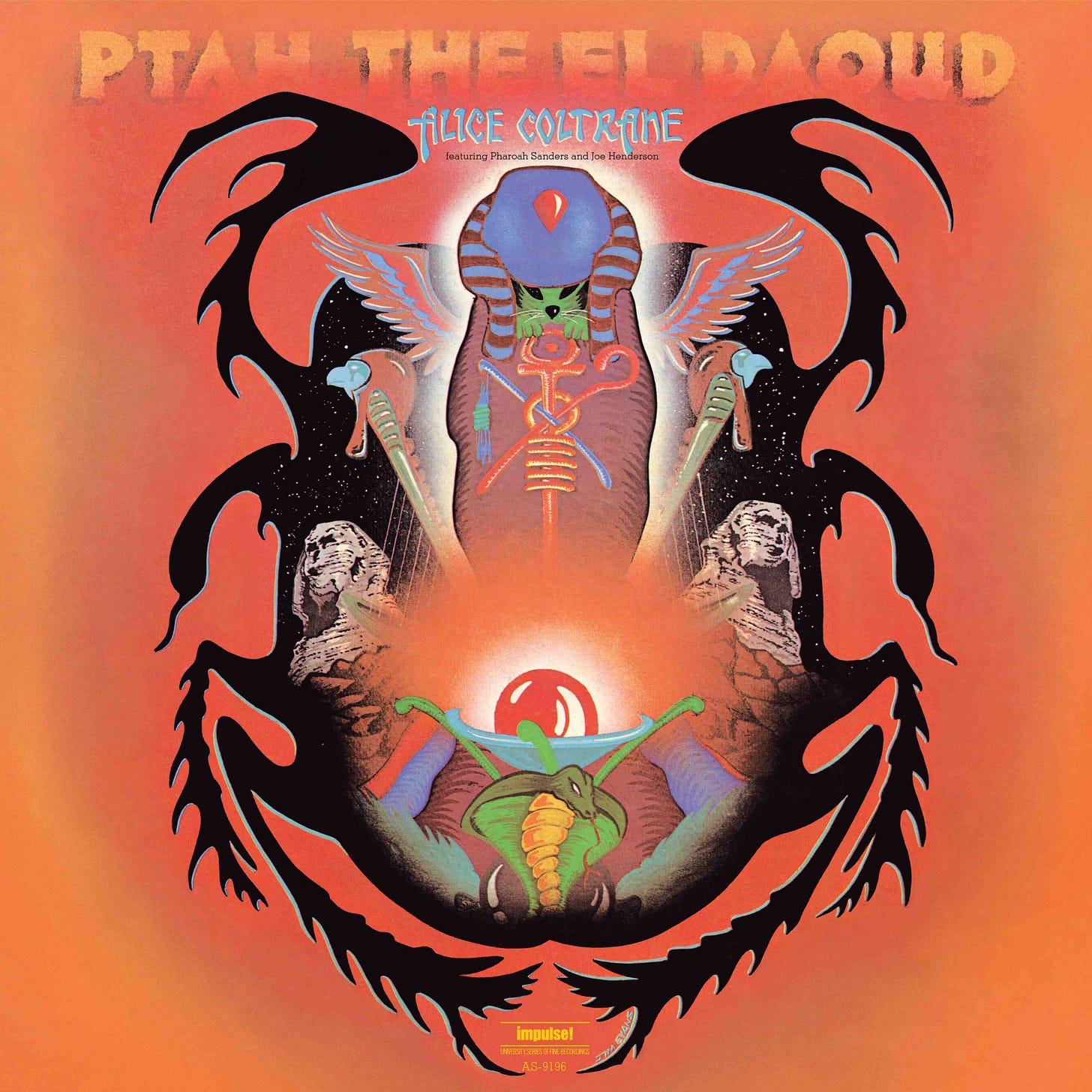

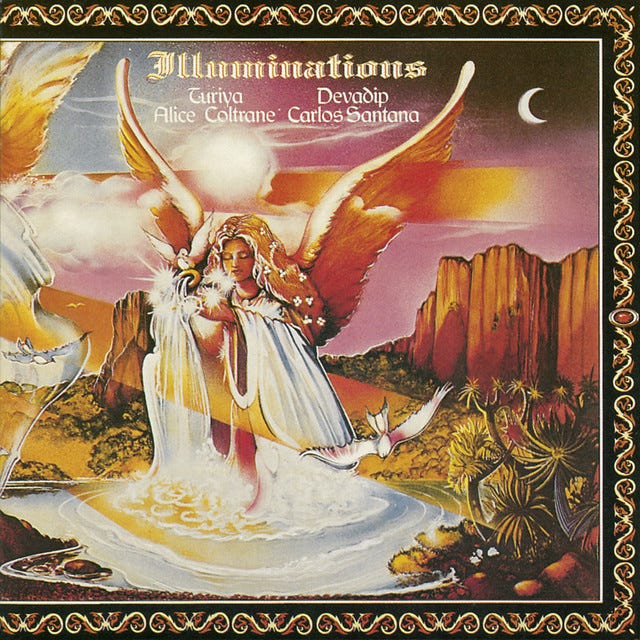

The album covers for Ptah, The El Daoud (1970) and Illuminations (1974) are heavily weighted in mystical symbolism. In an interview with Grammy.com, scholar Menzi Maseko states on Ptah, "What you see in the hieroglyphs are the names of God and of becoming. It says, 'The father of beginnings, the creator of the egg, the sun and the moon.' It's got the cobra at the bottom, which symbolizes cunning, superior intellectual capability and danger." On Illuminations, we see a more straightforward depiction of the angels Santana and Coltrane refer to in the collaborative album.

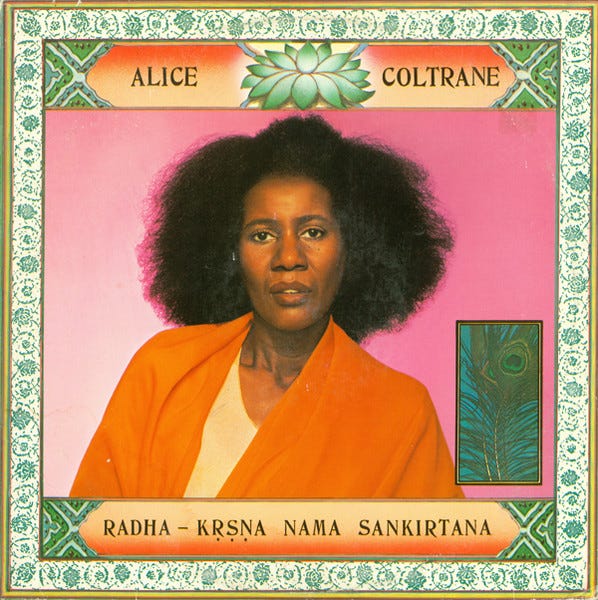

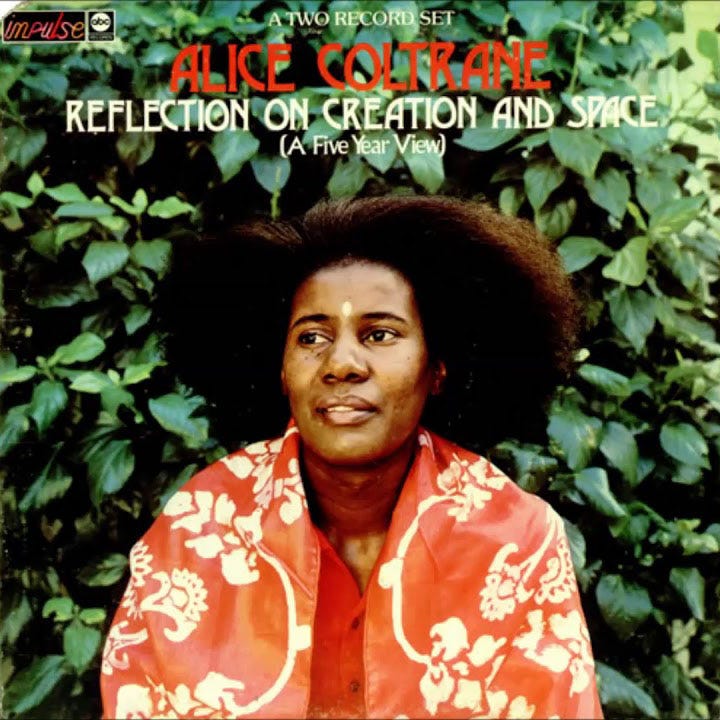

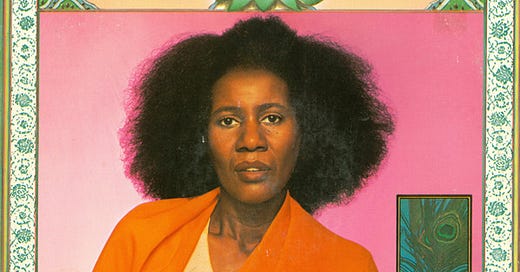

In photos and on her album covers, Alice is regularly documented and associated with the color orange. Highly intentional, it is the signature hue of Hindu spiritual leaders, swaminis. In a new exhibit at the Hammer Museum, entitled Alice Coltrane, Monument Eternal, orange accent walls guide the visitor through the gallery. She wears a saffron-like robe on the album covers of Reflection on Creation and Space, Eternity, Radha-Krsna Nama Sankirtana, and Transcendence. Even on Monastic Trio, we see her in an orange top with matching hoops. Saffron, one of the three shades of the Indian flag, stands for “courage, sacrifice and the spirit of renunciation,” as written in The Secret Lives of Color by Kassia St. Clair.

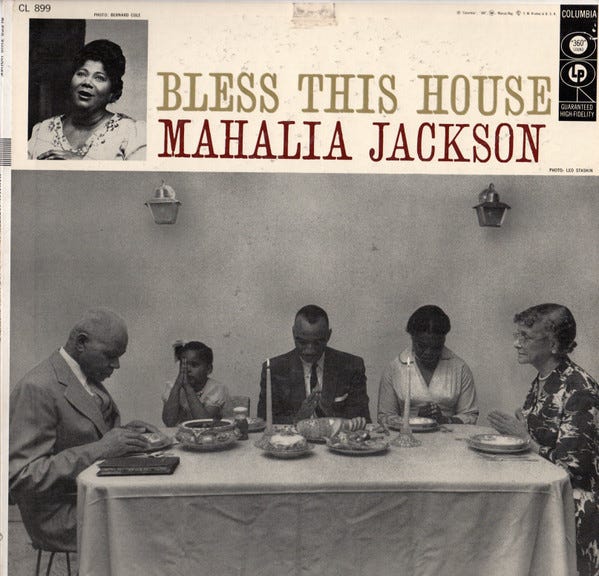

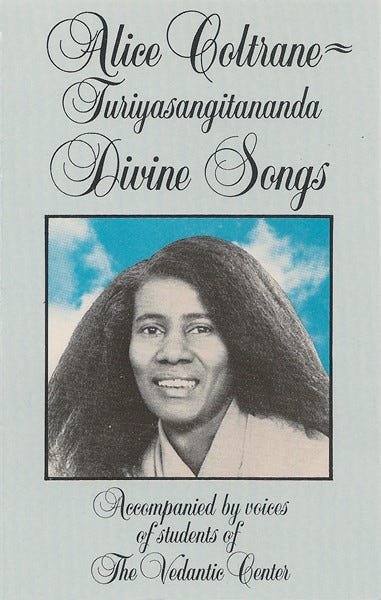

Some of Coltrane’s last releases were cassettes released via her ashram. They explore the interplay between her gospel roots and South Asian influences. This full circle moment makes me think of the imagery Coltrane must’ve witnessed in her upbringing, like the early album covers of gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. Her debut album, Sweet Little Jesus Boy (1955), features a black and white photo of Jackson embracing a young boy while looking up to the heavens. On Bless This House (1958), we see a photo of a family seated at a table, heads turned down in prayer. A portrait of religion across generations.

While Jackson’s black and white photographs are due to the technology of the time, it only juxtaposes how much vibrancy Alice channeled into her album covers. Find more of her transcendent imagery below:

The Art of Cover Art is a free educational and inspirational resource. If you have $5/ month to spare, it would be super helpful in furthering my research. Or, if you think a friend might enjoy this newsletter, the best way to pay it forward is by sharing!

Her music and art builds on what her late husband did, but expands into roads even he might not have taken.