A Brutally Honest Album Cover

How the art of Rage Against The Machine and Käthe Kollwitz speak to us in times of war.

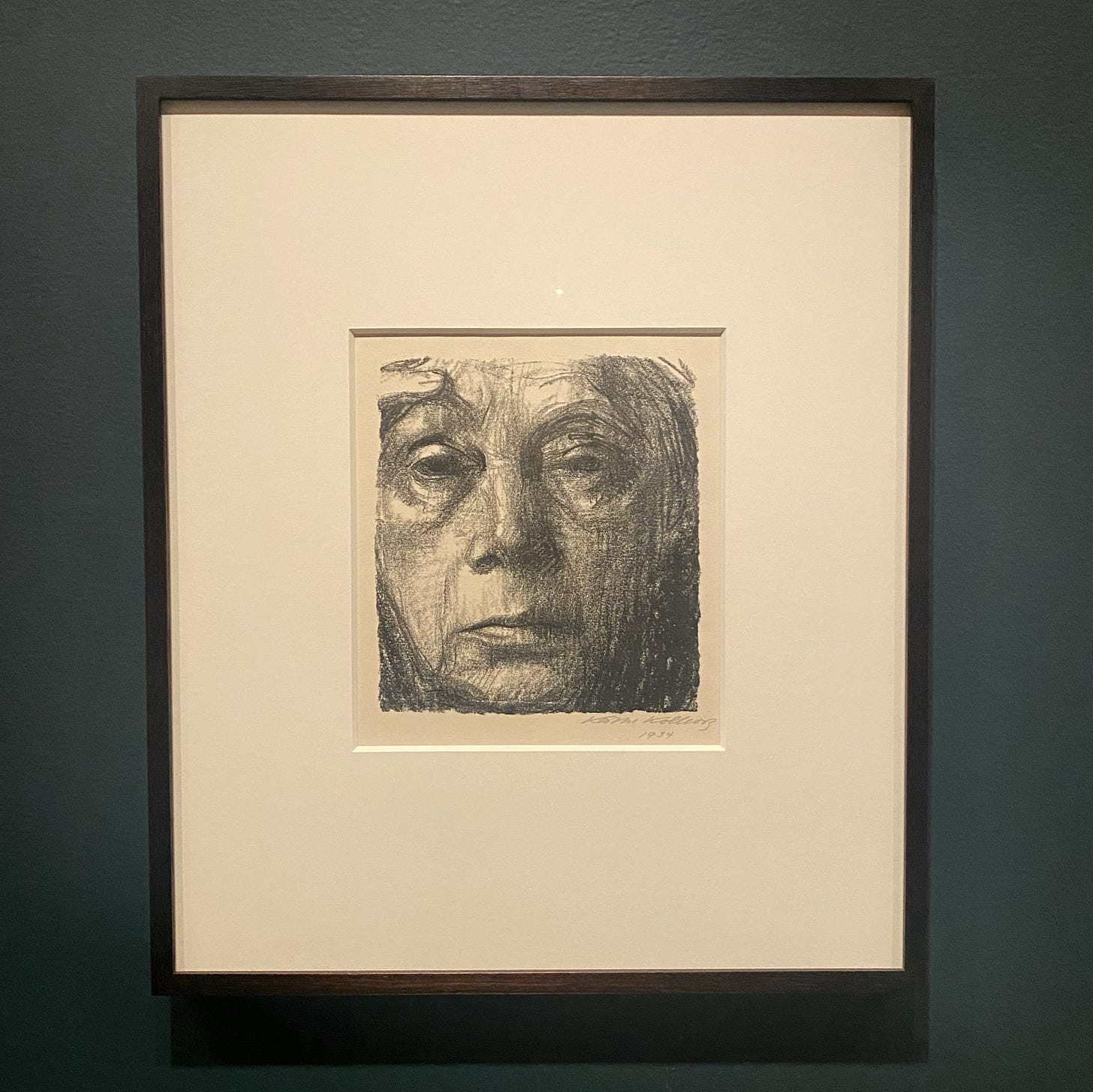

Last month, I visited the Käthe Kollwitz exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Working in Berlin in the early 20th century, Käthe depicted working-class citizens in scenes of intense labor, poverty, sickness, and death through painstakingly detailed drawings. The show and Kollwitz’s work are unabashedly dark, an early form of modern-day photojournalism.

Her art feels eerily familiar, reminiscent of images that have been flooding our news reports over the past 7 months. Amidst her documentary pieces, Käthe also drew self-portraits throughout her life. As the artist ages, the viewer can see through these depictions how the actions of the German government and the tragedies of two wars have physically affected her. But even while tortured by her own personal pain (Kollwitz lost her son Peter in combat in 1914), Käthe continued her practice of documenting injustice. As cited by MoMA, she wrote, “I have no right to withdraw from the responsibility of being an advocate… It is my duty to voice the sufferings of men, the never-ending sufferings heaped mountain-high.”

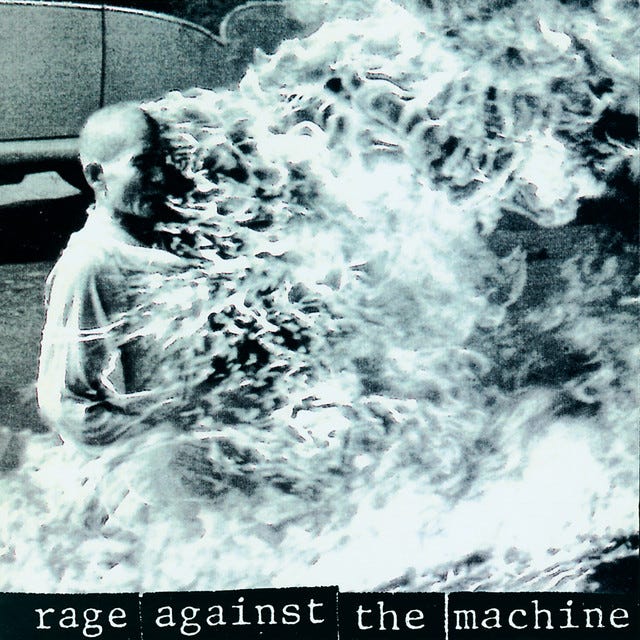

The same morning I visited MoMA, a man named Maxwell Azzarello self-immolated outside the downtown Manhattan courthouse where Donald Trump’s hush money case was taking place. Just two months prior, Aaron Bushnell self-immolated outside of the Israeli Embassy in Washington, D.C., in protest of the war in Gaza. Their actions immediately made me think of the photograph of Buddhist monk Quang Duc ablaze in an intersection in Saigon, Vietnam, taken by Malcolm Browne in 1963. Quang Duc’s self-immolation was performed as an act of protest against Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and his religious persecution against Buddhists. In an interview with TIME Magazine, Browne shares the story and accompanying images leading up to the hailed photo.

In 1992, California hardcore rock band Rage Against The Machine bought Browne’s photograph to cover their eponymous debut album. Upended by the aftermath of Rodney King’s unforgivable beating by Los Angeles police forces and the riots that ensued, the group wrote ten tracks that speak against police brutality and racism, most famously, “Killing In The Name.” It’s interesting to think how the late monk would feel about his image being used in a commercial capacity, albeit for a group who shared similar values. The band, of course, came under controversy for the purposefully graphic visual, but as a result, further cemented Quang Duc as a global symbol of revolution for the younger post-Vietnam generation.

Music, at its core, is inherently political, and there have been many great albums like Sly & The Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971), Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988) and Bikini Kill’s Pussy Whipped (1993) that are in conversation with RATM’s debut LP. But none of these album covers emit the same visceral emotion as being forced to confront the image of a fellow human being sacrificing their own life. Like Kollwitz’s work, Rage Against The Machine makes me shiver.

As time goes on and more music is released, the cover of Rage Against The Machine will most likely stand alone in its ferocity due to the accessibility of war in the 21st century. Joanna Bourke, the editor of War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict, wrote for CNN, “The theme and mood of war art has undergone major shifts over the past two centuries. Prior to the twentieth century, war artists were more likely to depict heroic tales rich in religious imagery, such as the ‘Massacre of the Innocents’ and the ‘Passion of Christ.’ Nineteenth-century British painting reveled in depicting decisive military maneuvers taking place in sumptuous battlefield landscapes.”

Before the end of the 20th century, art was used as a vessel for informing the world of unseen horrors and tragedies. Now, with technology expanding, our need for “war art” has declined in favor of real-time footage on our phones. We no longer need to uphold this sort of imagery to the level of “art” because we’ve become so used to seeing it mixed in with Instagram ads on our phones. But that might also be where we are mistaken. In these times of terrible war and heartache, honest art is what makes us remember the atrocities of the past and pay attention to those happening right now.

The Art of Cover Art is a free educational and inspirational resource. If you have $5/ month to spare, it would be very helpful in furthering my research. Or, if you think a friend might enjoy this newsletter, the best way to pay it forward is by sharing!